| NONESUCH SILVER PRINTS | |

| Unique photographs on silver from the 1950s and 1960s | ||

| from Nonesuch Expeditions |

THE

ART OF SILVER |

The Art of Silver 2015 - Tony Morrison looks back on a lifetime with a camera

The beginning As a fifteen year old with a leaning towards science I was asking questions. How did cinema film work? - I had been given some broken frames by the projectionist of a local cinema - Or how did those old family photos come to be in our album? What was the science behind the images? And most importantly, how could I do the same? The 'Photographic Chemists'

By the time I was studying at university most post-war import restrictions had been lifted; these Photographic Chemist shops were on the wane and being replaced by specialist stores resembling Aladdin's Caves of photo gear. But - back to the beginning. At our Photographic Chemists I found all the essential ingredients for making pictures from scratch, just as the Victorians did in the early 1800s. In the course of a few months my parents' bathroom shelf was complete with bottles of nitric acid, hydrochloric acid otherwise known as 'spirits of salts', sodium hyposuphite aka 'hypo', gallic acid, 'metol' - said to be nasty for the hands, 'pyro' - short for pyrogallol, potassium ferricyanide - Yes.... cyanide, silver nitrate, iodine crystals and eventually much more. Oh… And a very stained, once white laboratory coat - which soon matched my fingers and the bathtub, by then turning a gentle brown.

The know- how The know-how needed for making everything to create photographs was published in Victorian times and I could find plenty of old books on the shelves of the Town Library. Most photo books and magazines of the 1800s were filled with formulas or recipes.

The Watkins Manual

Photography as We know It

Lacock with its Abbey takes its name from the old English word Lacuc meaning 'streamlet'; it is some 32 miles from the city of Bristol in the west of England and the River Avon is nearby. The Abbey stood at the centre of the extensive Lacock estate that included the village and surrounding land. As a student at the University of Bristol I joined the Photo Society's outings for a 'pie and pint' lunch in the Lacock village pub The Red Lion. These annual trips were a welcome change from our relentless round of science tutorials.

Knowledge of silver By about 1825 anyone searching for a light sensitive substance knew that compounds of silver such as silver with chlorine reacted and could record simple images on paper - hence my purchase of silver nitrate and hydrochloric acid.

Henry's mother was Lady Elizabeth Fox-Strangways, daughter of the second Earl of Ilchester, another landowner and also a Member of Parliament. The family estate with fine gardens and avenues of trees surrounded the impressive Melbury House built in 1545. Melbury House glows from sunlight falling on its beautiful golden brown Ham Hill stone taken from Ham Hill across the county boundary in Somerset, another of the landmarks I used when cycling. William Henry Fox Talbot

It was thanks to his mother who turned around the fortunes of the Lacock estate that he was able to live in the Abbey and be comfortably placed financially to be an inventor. As such he preferred to use the name Henry Talbot, or simply H F Talbot on letters, though more formally, including for his patents, he included the name 'Fox'.

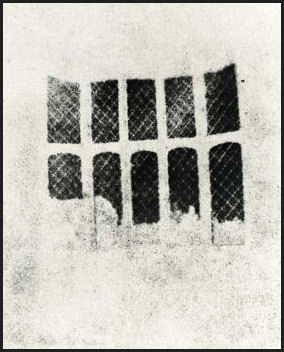

The lattice window It was not the only Eureka moment in photography but for Henry Talbot it was, when in 1835 he saved an image of the latticed Oriel Window in the Abbey's south gallery. Latticed windows were made with multiple panes held together in frames, often squares or diamonds of malleable, rust resistant metal.

The second image in New York and Online Henry Talbot made a second image and that is conserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and available for anyone to see online - links below. The Museum says it is the oldest photograph in their collection with a date of 1835 and it is credited to William Henry Fox Talbot.

So how did Henry Talbot do it? On the one hand he had the practical experience of the Camera Obscura a device loved by early Victorians. But while pictures from a Camera Obscura could be seen on a wall or table they could not be saved. Some Camerae Obscurae were set in specially built rooms or buildings. Inside a Camera Obscura where it was dark a view of the outside was directed to a wall or screen by light rays entering through a small hole in a wall or roof. Often the holes were known as 'pin-holes' as for the optical properties they had to be very small.

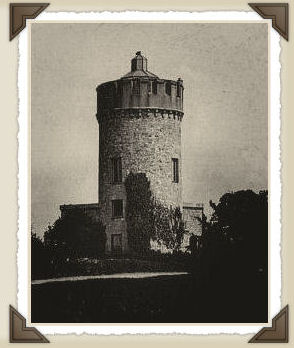

The optics of the simplest Camera Obscura meant that the image would be upside down - and even worse the image was mirrored left to right. So for the viewers who may have paid for the experience the scene was turned the right way up and corrected right to left using a mirror. Magic! The tills soon rang. Here on the left is the Clifton Observatory in Bristol a Camera Obscura built in 1828 from a derelict mill. Henry Talbot set up several of the tiny Camaræ Obscuræ in the Abbey which the family nicknamed 'mouse-traps'. Inside these little boxes Henry Talbot laid paper sensitised with a silver compound in the path of light rays from the window. So far so good - a miniature Camera Obscura - sensitised paper and hey presto, albeit after a long exposure to light, an image was created. The next stage and most valuable, was to 'fix' the image so it could be kept in daylight, and that meant stopping the reaction within the silver compound. Henry Talbot found a way. The original image a little more than 2.5cms square was a 'negative', as the bright light from the glass panes left dark patches and a lighter window frame. Henry Talbot then repeated the process. He took the 'negative' and pressed it against another piece of sensitised paper and left it in sunlight. The second piece of paper was then treated with salt to stabilise the 'positive' image. As his experiments moved on successfully Henry Talbot was very aware that he had cracked the problem and he knew other inventors would be looking to do the same. A spot of industrial espionage was always possible and so he found himself in a Catch 22 situation. To get the kudos as discoverer he had to make his process available to the scientific world and that meant 'publishing' in a reputable scientific journal. Clearly the secret would then be out. Other processes were emerging in Europe and in January 1839 Henry Talbot heard of a process invented by Louis Daguerre in France who published in the same month. Henry was prompted to pluck up courage and present his work in a written description to the prestigious Royal Society in London on Thursday 31st January 1839. As H Fox Talbot Esq - he wrote of the achievement. 'Some account of photogenic drawing or, the process of which natural objects may be made to delineate themselves, without the aid of the artist's pencil............In the summer of 1835 I made in this way a great number of representations of my house in the country; which is well suited to the purpose, from its ancient & remarkable architecture. And this building I believe to be the first that was ever yet known to have drawn its own picture.' CLICK to read or dowload the PDF for the full account If you have time it is worth reading, more from the point of what is missing than what it contains. Henry Fox Talbot made no reference to the chemistry for fear of giving away too much so the academicians were none too pleased. The omissions have given rise to endless haggling over who could claim being first to invent a usable photographic process. My bet is on Henry. From here on it was a race between the inventors to perfect and commercialise the process usually using silver compounds but not always. Metals such as chromium, copper and mercury came into other equations. Daguerre used a highly polished silver surface usually on a copper plate, but the process was sufficiently complicated that making multiple copies was not commercially viable. Within two years Henry Talbot had fine-tuned his discovery and in early 1841 he patented what he named the Calotype Process. British Patent 8842 in the name of William Henry Fox Talbot of Lacock Abbey gives a very detailed description. My Invention of "Improvements in Obtaining Pictures, or Representations of Objects" Henry's 'Candles and fires' may need a re-think in present Health and Safety conscious times. But have a go. Here's the Patent CLICK to read or download PDF Patent 8842 Using paper sensitised with solutions of Potassium iodide and silver nitrate and additionally sensitised with a gallic acid compound of silver, Henry Talbot reduced the time needed for exposure to light. The exposed or 'latent' image in the paper was enhanced with gallic acid and once the image was stabilised the process was repeated on fresh paper to get a positive 'print'. Henry Talbot made photographers pay a fee to use his patented process. Do I hear moans about how software is charged today? But eventually a burgeoning band of photographers rebelled and there was a court action in 1854. Henry won his claim to be the inventor but lost his claim against the photographer who infringed his patent.

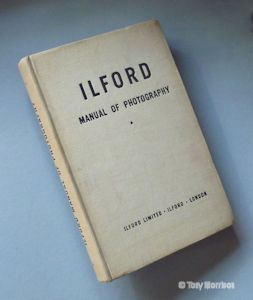

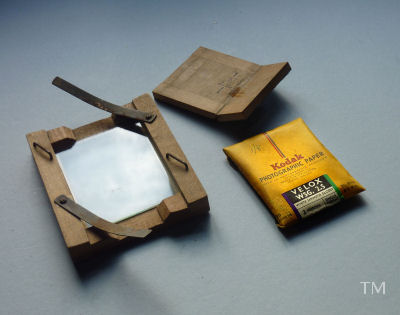

In my bathroom-darkroom and thinking of that Victorian race I sloshed about with my home-sensitised paper. I made it with the best white writing paper in the house brushed with a solution of silver chloride and then silver bromide. I even tried stabilising the surface with egg white. Then I used 'metol' for development without any daylight - just a candle. I dreamed little of patent infringements but more of trying more exciting chemicals including platinum and gold. It was a bit akin to Photo Lego adding a gold part but my post-WW2 Britain Wish List budget couldn't stretch. Much of the techie info was in the Ilford Manual of Photography an absolute 'must' for any photographer in the 1950s. When I began messing about with silver my intention had been to retrace Henry Talbot's steps and make a pin-hole box and then a positive print. I had some success even with a pin-hole camera and using a commercial Kodak paper but eventually the slowness and uncertainty of the process turned me to ready-made film with its clear flexible base coated with a silver-based light sensitive layer. I wanted to get on with taking photographs and stop playing with chemistry. I returned to some of it later. Roll film was first introduced in the 1890s and those sold in my favourite high street Photographic Chemist were made mostly by Kodak, Ilford or Dufay, by then household names. As first steps in film picture making I exposed several rolls in an old camera that belonged to my mother.

This was a 1930s box camera. Box cameras were Victorian inventions based on the Camera Obscura and as the name suggests they were not much more than a box with a hole in one side. The original pin-hole idea was upgraded by the addition of a very simple lens and instead of an open hole or patch covering the lens the light was allowed to enter by opening a shutter. The Box camera was aimed at the mass market and was inexpensive and reliable. The shutter on the Comet was opened and closed by a lever with a click of about 1/30th of a second. Inside the box the sensitised film was rolled past the rear wall or film 'plane' permitting me to make several pictures on one roll. The Comet has a small external and light-proofed key to wind the film from a spool at the bottom to another spool in the top. My film choice was Ilford Selochrome 120 'Ortho' which gave me eight pictures each 6cms by 9cms quoted as 2¼ inches by 3¼ inches. In most box cameras the 1/30th of a second is not enough to freeze movement so someone walking appears blurred. Also the lenses are not much good in dull light so the best that can be said is the exposure given to the film is a compromise. To get the image from film to paper was a process that had not changed in principle since Henry Talbot's day. Ortho film was not sensitive to reddish light so I could develop in open dishes in a darkened room. I then washed the negative image in water before fixing it in a solution of hypo so it could be viewed in daylight. Even in the 1950s the fixers were similar to those of a hundred years earlier - with variations naturally, and price increases. When my negatives were dry I used a wooden frame to clamp the negative to sensitised paper to make prints of the same size.

My printing frame was an Ensign, made in Britain. The simplest paper I could get was Printing Out Paper (POP) such as Kodak Velox WSG 2 aka White Smooth Glossy - normal contrast, single weight (not thick paper). In the 1950s this packet of 25 sheets cost one shilling and eight pence or the equivalent of 8.5 pence in decimal British money.

On the left - I took a a single sheet of the Velox paper - sixty years old and exposed to subdued sunlight for 1.5 hours with a coin shading the centre. This was the colour change without any development. Out of the packet the old paper curled but the glossy surface was just as it would have been when fresh

After an intermediate wash I 'fixed' the paper using a solution of hypo to stop any further reaction in the silver. Now for the critical bit - in each process I had to wash the prints with a thorough sluicing in water to eliminate all the chemicals. If the washing was too short and chemicals were left in the prints they often turned brown even in an album. As I moved on I used Panchromatic film which was sensitive to all lights and had to be developed in total darkness. Once I got the hang of the development times I tried printing in the same frame but with a more sensitive paper exposed briefly to artificial light, and then developed and fixed. 1953 and an Old Bridge

But it is a record of the River Tone in flood and of a very old bridge that became my test site and the negative is perfect even after more than sixty years in a drawer. By this time I had made an enlarger or device that would project an image onto a larger sheet of sensitised paper and be processed as before. The next steps

The Kodak Ball Bearing Shutter with various patents from 1910 could be set for clear skies, brilliant skies and moving objects. It could even be kept 'open' by using finger pressure through a cable control. The adjustment is made by a small lever at the top. At the bottom, another lever set the size of the opening ['aperture'] controlled by an iris diaphragm - just visible as the central ring. Behind that is the lens. When it was on the camera I took a photo depressing the release here on the left of the picture - or with my right forefinger. With a spot of parental ingenuity and care I converted the camera to use the same film as the Comet. But after just two rolls of film in which I saw the advantages of controlling the shutter my mind was set on something even more sophiticated and as another present I was given a German folding camera, a Baldix, one of the first models to come into post war Britain.

But the Baldix had a 'top' shutter speed of 1/300th of a second so I could use it for sports pictures - here a school race in 1954 Then I joined up with a friend from our village, David Cole, and together we experimented with colour. It was expensive so the experiments were short lived and instead we tried the dozens of black and white film / developer /printing paper/ developer combinations. 'How do you rate Ilford's latest with the new one from Kodak' and so forth. David went on with a scholarship to work for Kodak - he says he still prefers Ilford film. So fifty rolls later By my university years when - and I have to be honest - I spent more time expanding my interest in photography than studying, I moved on to better gear and a small but very adequate darkroom. Cash flow from occasional work for student sports clubs, graduates at graduation and the student newspaper gave me the chance to buy two new British made cameras in quick succession, first a Microcord soon which I soon traded in for a Microflex made by the same company - MPP [Micro Precision Products]. Both cameras were Twin Lens Reflex with effectively a second camera working through the top lens to a screen under a hood - here in the picture folded down. Now I could see and manually focus on an image before pressing the shutter The Microflex has been around the world with me a couple of times- it still works and is wonderful to use. Not many of these cameras were made as the post-war import restrictions were lifted and high quality German equivalents appeared. But the Microflex was built with a Taylor Taylor Hobson lens. TTH was a British lens maker of world renown. At about the same time I bought a light-meter so I coud set the lens acording to the light and the sensititivity of the film. The Weston Master lll was about 9.5 cms long and worked without a battery. Light entered behind the meter and affected a light sensitive cell which in turn gave a reading on the meter. The disc with the arrow was used for calibrating the correct exposure. It may sound awkward but after a few tests my mind, film and light seemed to work together.

My bathroom-darkroom of the 1950s filled with so many caustic chemicals was emptied over half a century ago and for many years the chemicals I used were pre-prepared and carried in my luggage - again I wonder how that would be appreciated at an airport check-in today. Most memorably on my Around the World university expedition May & Baker, a pharmaceutical company in Dagenham, Essex, supplied me with their internationally famous developer Promicrol and Amfix, their Ultra Rapid Fixer. Just occasionally I had black and white film processed by professional laboratories - overseas by Photo Sphinx in Beirut in 1962 and throughout the 1960s when in Lima, Peru by Walter O Runcie. Othewise in South America I relied on Casa Kavlin in La Paz. In London my printing was in either a simple home darkroom or at Roy Reemer's where an elderly woman, the receptionist, did the 'spotting' to get rid of dust marks on the prints. I always had a good welcome 'Hello Tony ... where've you been this time? And I still have a a clutch of Roy Reemer prints as good today as they were then. My old friend David Cole had a darkroom and also I could rely on the work of Robert 'Bob' Horner in Kensington, West London. Good printers and their art were a vital part of the 1960s photo scene. And now the question Why silver in this digital age when remarkable software converts colour digital to black and white and the marvel of giclée printing offers superb prints on a variety of paper and other surfaces? To answer I need to offer a few examples from my world of silver-based photography but first something special from Henry Talbot. A Calotype from 1844 Here is one of Henry Talbot's Calotype photographs which is kept in The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England.

The picture here is of a paper print made by Henry Talbot's process and the detail of the original paper negative shows well. You can see surprising detail of the ship in darker areas and typical paper negative mottling in lighter areas from 'see through' or the faint image of the paper negative. It is now over 170 years old and has survived because once carefully processed - and the point is - silver hardly changes. For naval historians this picture has been a mine of information about the Great Britain and for Bristol people it gives a very clear idea of the Floating Harbour of the era including a pebbly foreshore and background of wooded hills. Both are missing today.

For more about the Great Britain see Nonesuch Expeditions From very early efforts like this, the silver process evolved very quickly and the quality of the image improved. Silver offered challenges for the photographer to achieve a fine gradation where the specks of silver were hardly visible, or to join the 1960s rush for the grains to be visible. 'They must stand out like golf balls' - pictures had to be 'gritty' with a powerful image. For advanced printing on silver sensitised paper superb tonal ranges and hues were possible with gold toning, selenium toning, bromoil or the traditional sepia but with true depth of colour. Other processes such as platinum or gum bichromate were still being tried by some of my fellow Camera Club enthusiasts. I tried one oddball treatment known as Brometching to get a print that could have been a century old. Here are some of the variations

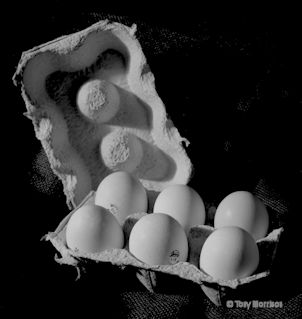

The Microcord had a 77.5 mm F3.5 Ross Xpres lens and I used a one [1] dioptre close-up lens. FP3 was superb in average lighting and gave a great range of tones. Look to the shine top right on the enlargement. This photo came from a vacation project for a local egg producer soon after the 'British Lion' marking had been introduced. The Lion was a symbol for British production with a code and freshness.

The downside of RXP was the near visible granularity of the silver sensitised layer or 'emulsion'. But this graininess was grabbed by enthusiasts and led to a genre of pictures with striking 'grainy blacks' and whites. This was on my Microflex camera at a University Drama Society production of Camino Real.

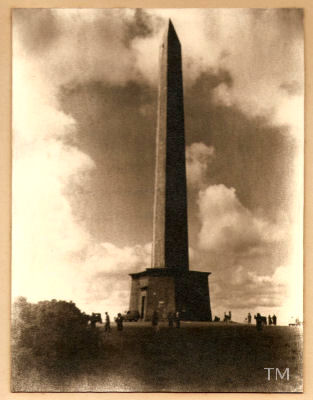

In the process of print making the image took up the uneven surface of the paper so giving an aged effect. Here the paper was Kodak Bromesko with a surface known as Ivory Fine lustre, lightly dappled and used because Bromesko yielded a soft brown image. The original negative was made on the Baldix camera using Kodak Plus X a medium speed film and exposed at 1/50th second at F 5.6 (F numbers were the way a lens was calibrated to allow more or less light to pass). In the camera I used a used a green-yellow filter to enhance the clouds. The Brometching process was the epitome of Witches' brewing - the print was over exposed in the enlarger which meant it was almost black in the developer stage which was also extended. Then after rinsing away the developer, the etching was done in a solution of salt, sulphuric acid and potassium permanganate. The image appeared slowly through the dark print and Hey Presto! - a Victorian classic was ready to be fixed in hypo and washed. This is the Wellington Monument in Somerset - completed in 1854 - the cars are a giveaway!

All these pictures are from silver negatives or silver prints in our collection and kept from damp they will last for centuries. Silver has been a name in image making since 1825 and will retain a timeless, lasting quality loved by collectors worldwide. Credits - with enormous thanks to Henry Talbot for a wonderful contribution to my life and to Alfred Watkins for some of his straight line thinking Notes

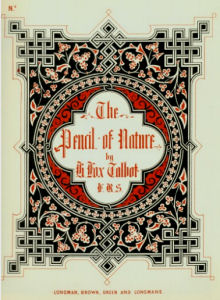

As H Fox Talbot FRS, Longman Green published a book about his silver process in 1844. The Pencil of Nature is available online with illustrations from The Gutenberg Project Henry or H F Talbot's letters are available as transcipts online from De Montfort University, Leicester, England Henry Talbot died on 17th September 1877 in his study at Lacock Abbey and was buried at Lacock. On

the south wall of the Chancel of St Cyriac's church with foundations in the 11th

century a memorial says Henry

Talbot left a modest sum of less than £12,000 British Pounds | |||||||

|

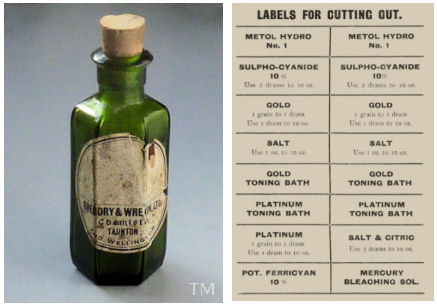

Luckily

in our small country town we had at least three 'Photographic Chemists' or shops.

The Photographic Chemists were a legacy of the Victorian era, not only serving

pills and potions for the ailing but also keeping stocks of photo paper, chemicals

for photography and a few pre-used cameras.

Luckily

in our small country town we had at least three 'Photographic Chemists' or shops.

The Photographic Chemists were a legacy of the Victorian era, not only serving

pills and potions for the ailing but also keeping stocks of photo paper, chemicals

for photography and a few pre-used cameras.  One

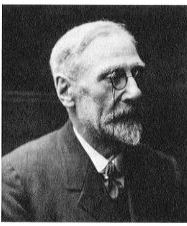

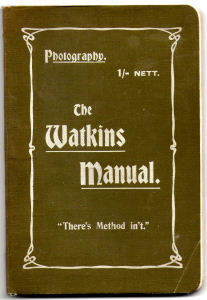

very popular source was The Watkins Manual written and published by Alfred

Watkins, a wealthy enthusiast who owned several businesses including a flour mill

in Hereford in the West Midlands of England. Like many Victorian photographers,

his interest started as a hobby but he moved on and left the world with a comprehensive

DIY for early photography. The first Watkins Manual was published in 1890

and went into eleven editions. The cover is of the Third Edition published in

1906.

One

very popular source was The Watkins Manual written and published by Alfred

Watkins, a wealthy enthusiast who owned several businesses including a flour mill

in Hereford in the West Midlands of England. Like many Victorian photographers,

his interest started as a hobby but he moved on and left the world with a comprehensive

DIY for early photography. The first Watkins Manual was published in 1890

and went into eleven editions. The cover is of the Third Edition published in

1906.  Watkins'

little book of 152 pages is only 175cm x 120cm and is packed with photo information.

Advertisements for the equipment he invented and marketed are at the end. It also

includes a precise record of some products of the era and their manufacturers,

for example Ilford Plates and Papers of All Dealers Ilford Limited London

E, and Wratten's London Plates. Later I came across both names, time

and time again as the firms had survived.

Watkins'

little book of 152 pages is only 175cm x 120cm and is packed with photo information.

Advertisements for the equipment he invented and marketed are at the end. It also

includes a precise record of some products of the era and their manufacturers,

for example Ilford Plates and Papers of All Dealers Ilford Limited London

E, and Wratten's London Plates. Later I came across both names, time

and time again as the firms had survived. The

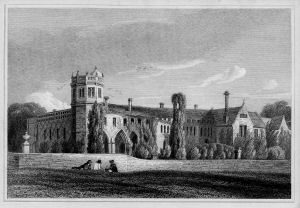

photography we know either in pixels or silver began not in some concrete and

glass security controlled hi-tech lab in California or Cambridge but within the

somewhat austere walls of a 13th century abbey.

The

photography we know either in pixels or silver began not in some concrete and

glass security controlled hi-tech lab in California or Cambridge but within the

somewhat austere walls of a 13th century abbey. The

breakthrough in photography is usually attributed to William Henry Fox Talbot.

He was the only son of William Davenport Talbot of Lacock Abbey, an Army Officer

saddled with debts. Henry was born in 1800 not at Lacock but in his mother's family

home in Melbury Sampford in Dorset, a neighbouring county and only 30 miles from

my home. Henry came into a world of affluence with excellent political and scientific

connections.

The

breakthrough in photography is usually attributed to William Henry Fox Talbot.

He was the only son of William Davenport Talbot of Lacock Abbey, an Army Officer

saddled with debts. Henry was born in 1800 not at Lacock but in his mother's family

home in Melbury Sampford in Dorset, a neighbouring county and only 30 miles from

my home. Henry came into a world of affluence with excellent political and scientific

connections.  William

Henry Fox Talbot was educated at Harrow School, where he was known to have experimented

with chemistry, apparently sometime resulting in explosions. He went on to Trinity

College, Cambridge where he studied Classics and won a prize for Greek verse.

For two years in his early thirties he was a Member of Parliament. By the time

he was thirty-five his father was dead and his mother remarried.

William

Henry Fox Talbot was educated at Harrow School, where he was known to have experimented

with chemistry, apparently sometime resulting in explosions. He went on to Trinity

College, Cambridge where he studied Classics and won a prize for Greek verse.

For two years in his early thirties he was a Member of Parliament. By the time

he was thirty-five his father was dead and his mother remarried.  The

original image or as now known the 'negative' made in August 1835 is small and

faded and a copy is displayed at the Fox Talbot Museum in Lacock. Sadly a bit

too far to travel for many photographers - even those on a pilgrimage.

The

original image or as now known the 'negative' made in August 1835 is small and

faded and a copy is displayed at the Fox Talbot Museum in Lacock. Sadly a bit

too far to travel for many photographers - even those on a pilgrimage. The

Camera Obscura - the name Camera lives on

The

Camera Obscura - the name Camera lives on Back

in my bathroom-darkroom with a pin-hole camera

Back

in my bathroom-darkroom with a pin-hole camera The

Comet

The

Comet

The

printing frame

The

printing frame Once

OK, I developed the paper in a solution made from a Kodak powder - for bluish

black tones Kodak suggested D 158 and for a neutral black it was Special Developer

D 163 and for colder black it was D 163 with 'Kodak Anti Fog' - all serious gobbledegook

but it worked. Mostly I used plain D !63.

Once

OK, I developed the paper in a solution made from a Kodak powder - for bluish

black tones Kodak suggested D 158 and for a neutral black it was Special Developer

D 163 and for colder black it was D 163 with 'Kodak Anti Fog' - all serious gobbledegook

but it worked. Mostly I used plain D !63. Here

is a picture I took on the Comet in Somerset, England in 1953. The shortcomings

of the low cost Box camera are obvious - the picture is not sharply focused at

the edges though the centre is OK. In the dull light of winter and misty rain

the fixed opening of the lens and the fixed 1/30th of a second combination was

well beyond the film's limit.

Here

is a picture I took on the Comet in Somerset, England in 1953. The shortcomings

of the low cost Box camera are obvious - the picture is not sharply focused at

the edges though the centre is OK. In the dull light of winter and misty rain

the fixed opening of the lens and the fixed 1/30th of a second combination was

well beyond the film's limit. Next

I received a gift from an elderly aunt of a 1920s Kodak Autograph camera which

used 'Post Card' size roll-film.

Next

I received a gift from an elderly aunt of a 1920s Kodak Autograph camera which

used 'Post Card' size roll-film. The

film for the Baldix was the same size as I had been using in the Comet but each

roll gave twelve pictures. The lens and shutter combination could be adjusted

to most conditions with a flash synchronisation added. And most useful to me was

that it folded with a light tight cloth bellows between the lens mounting and

the body, so it was flat. It was easy to carry and for three and a half years

the Baldix came everywhere.

The

film for the Baldix was the same size as I had been using in the Comet but each

roll gave twelve pictures. The lens and shutter combination could be adjusted

to most conditions with a flash synchronisation added. And most useful to me was

that it folded with a light tight cloth bellows between the lens mounting and

the body, so it was flat. It was easy to carry and for three and a half years

the Baldix came everywhere. The

Baldix saw me through my schooldays with an entry into the local Camera Club,

whose members were largely well-heeled senior townsfolk who owned the crème

de la crème of gear.

The

Baldix saw me through my schooldays with an entry into the local Camera Club,

whose members were largely well-heeled senior townsfolk who owned the crème

de la crème of gear.

This

is the Steamship Great Britain, an iron ship created by the genius engineer

Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Henry Talbot took the picture probably in May 1844 in

Bristol at the Floating Harbour where the ship was being completed after the official

launch attended by Prince Albert, Consort of Queen Victoria.

This

is the Steamship Great Britain, an iron ship created by the genius engineer

Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Henry Talbot took the picture probably in May 1844 in

Bristol at the Floating Harbour where the ship was being completed after the official

launch attended by Prince Albert, Consort of Queen Victoria.

1957

This was shot on a British made Microcord camera using Ilford FP3 a film with

medium speed [rated 29º].

1957

This was shot on a British made Microcord camera using Ilford FP3 a film with

medium speed [rated 29º].

1960

In the mid 1950s Kodak introduced Royal X Pan film which was reckoned to be the

World's fastest film - meaning it could be used in very low lighting.

1960

In the mid 1950s Kodak introduced Royal X Pan film which was reckoned to be the

World's fastest film - meaning it could be used in very low lighting.

1955

I am including this print as it is my only surviving example of an old silver

process known as Brometching.

1955

I am including this print as it is my only surviving example of an old silver

process known as Brometching. Henry

Talbot was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on March 17th 1831 for his work

in mathematics and light. He published nine academic papers. The formal letter

of election was addressed to Henry Fox Talbot Esq.

Henry

Talbot was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on March 17th 1831 for his work

in mathematics and light. He published nine academic papers. The formal letter

of election was addressed to Henry Fox Talbot Esq.